4.2 Hypothesis Testing for mean \(\mu\)

4.2.1 Objectives

By the end of this unit, students will be able to:

- Formulate claims about a population mean in the form of a null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis.

- Conduct t-tests for testing claims about a single population mean based on one sample and paired samples.

4.2.2 Overview

Inference for a mean follows the same high-level path as inference for a proportion: state hypotheses, compute a standardized statistic, obtain a p-value from a reference distribution, and compare to a pre-specified significance level \(\alpha\). Because the population standard deviation \(\sigma\) is rarely known, we estimate it with the sample standard deviation s and use the \(\textbf{t distribution}\) with \(df=n-1\). This choice reflects the extra uncertainty from substituting s for \(\sigma\).

One-Sample t-Test:

When to Use the one sample t-Test is listed below when:

You have a single random sample of quantitative data.

You want to test a claim about the population mean \(\mu\).

Conditions for use:

Independence: observations arise from a simple random sample, random assignment, or sampling less than 10% of the population.

Normality: for small n, data should be roughly symmetric with no extreme outliers; for n \(\ge\) 30, the t-test is robust to moderate skew.

Steps in Hypothesis Testing

- State the Hypotheses

\[H_0: \mu = \mu_0 \qquad \text{vs.} \qquad H_A: \mu \ne \mu_0\]

Compute the Test Statistic

Using sample size n, mean \(\bar{x}\), and standard deviation s:

\[T = \frac{\bar{x} - \mu_0}{s / \sqrt{n}}, \qquad df = n - 1\]

Find the p-value

The p-value represents the probability of obtaining a result as extreme or more extreme than the observed one, assuming H_0 is true.

Use R functions:

Left-tailed: pt(t, df)

Right-tailed: pt(t, df, lower.tail = FALSE)

Two-tailed: 2 * pt(-abs(t), df)

Make a Decision Compare the p-value to the significance level \(\alpha\) (commonly 0.05):

If \(p \le \alpha\): reject H_0 → sufficient evidence for H_A.

If \(p > \alpha\): fail to reject H_0 → insufficient evidence for H_A.

Paired-Sample t-Test

Paired designs arise when each subject (or matched unit) provides two related measurements — for instance, before and after treatment. We compute the difference for each pair:

\[d_i = X_{1i} - X_{2i}, \qquad i = 1, 2, \ldots, n\]

Then analyze these differences as a single sample.

Hypotheses

\[H_0: \mu_d = 0 \qquad \text{vs.} \qquad H_A: \mu_d \ne 0\]

Test Statistic

\[T = \frac{\bar{d} - 0}{s_d / \sqrt{n}}, \qquad df = n - 1\]

Example: Trader Joe’s vs. Safeway Grocery Prices

In a previous local study, researchers found that Trader Joe’s prices were, on average, lower than those at Safeway for similar grocery items in 2015. Nearly a decade later, both stores have adjusted to inflation and competition from online retailers. We wondered: How do the prices compare today?

We sampled 68 common grocery items sold at both Trader Joe’s and Safeway. A portion of the dataset is shown below, with prices in U.S. dollars.

| item_number | item_name | safeway | trader_joes | price_difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Organic milk (1 gal) | 5.29 | 4.99 | 0.30 |

| 2 | Brown eggs (dozen) | 4.19 | 3.79 | 0.40 |

| 3 | Peanut butter (16 oz) | 3.99 | 3.49 | 0.50 |

| … | … | … | … | … |

| 68 | Greek yogurt (pack 4) | 6.59 | 5.99 | 0.60 |

We define the paired difference as:

\[\text{Difference} = \text{Safeway Price} - \text{Trader Joe's Price}\]

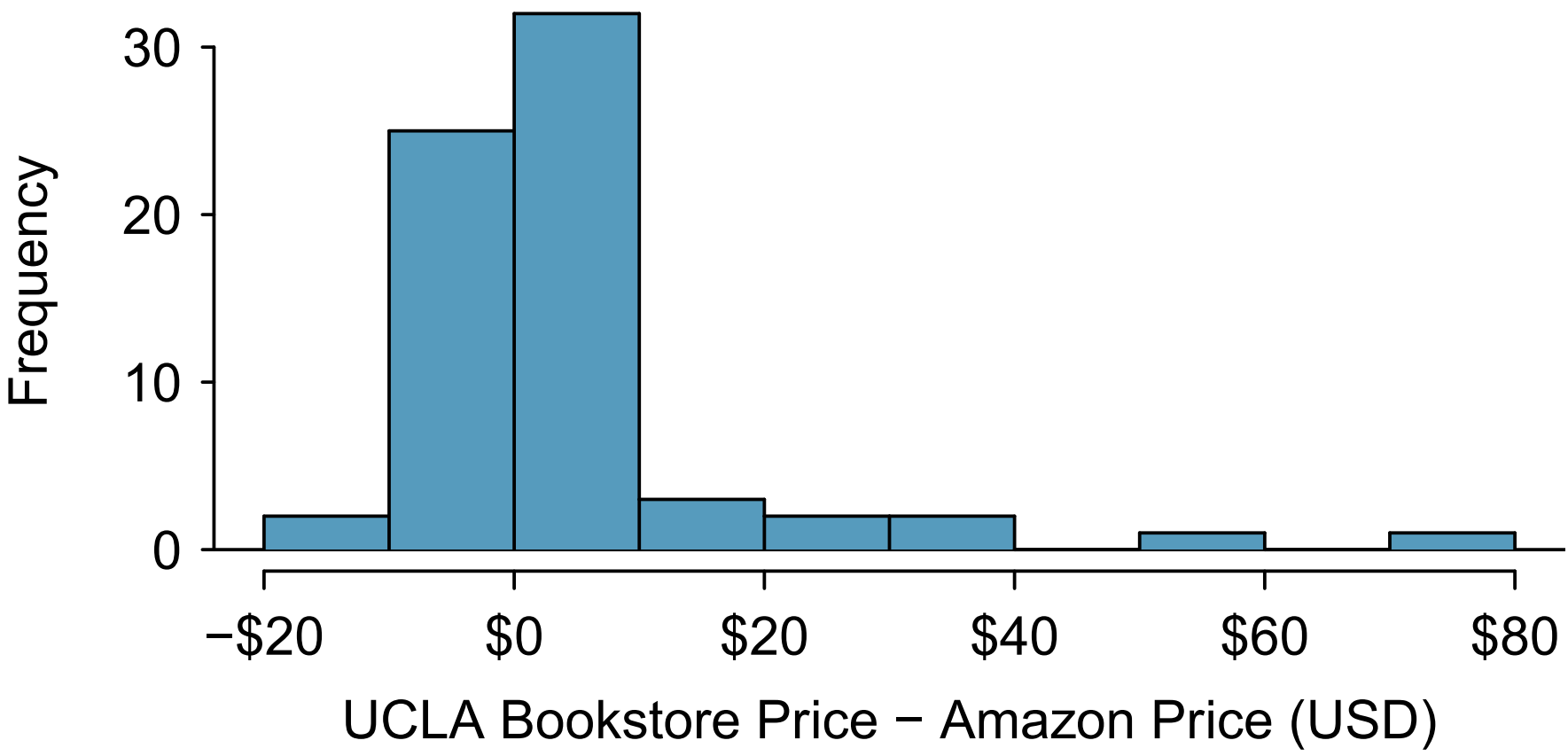

Positive differences indicate that Safeway is more expensive. A histogram of the price differences is shown below:

Sample statistics:

\[n_{diff} = 68, \quad \bar{x}_{diff} = 0.58, \quad s_{diff} = 1.79\]

We test whether the average price difference is zero:

\[H_0: \mu_{diff} = 0 \quad \text{vs.} \quad H_A: \mu_{diff} \ne 0\]

Compute the standard error and test statistic:

\[ SE_{\bar{x}{diff}} = \frac{s{diff}}{\sqrt{n_{diff}}} = \frac{1.79}{\sqrt{68}} = 0.217\\ T = \frac{\bar{x}{diff} - 0}{SE{\bar{x}_{diff}}} = \frac{0.58}{0.217} = 2.67, df = 67 \]

The two-tailed p-value corresponds to the shaded tails in the \(t_{67}\) distribution below

## [1] 0.009509096Paired Confidence Interval

The \((1 - \alpha)100%\) confidence interval for the mean difference is:

\[\bar{d} \pm t^*_{df} \frac{s_d}{\sqrt{n}}\]

n <- 68

dbar <- 0.58

sd_d <- 1.79

df <- n - 1

se_d <- sd_d / sqrt(n)

conf <- 0.95

t_star <- qt(1 - (1 - conf)/2, df = df)

ci <- c(dbar - t_star*se_d, dbar + t_star*se_d)

ci## [1] 0.1467277 1.0132723Interpretation: We are 95% confident that the average difference in prices (Bookstore - Amazon) falls within this interval. Since the interval is entirely above 0, bookstore prices tend to be higher.

Practical Guidelines:

Verify conditions: Independence and approximate normality (of raw data or paired differences). For \(n \ge 30\), the t-procedure is generally robust to mild skewness.

Predefine direction: Choose between two-sided and one-sided tests before analyzing data.

Report clearly: Always present t, df, p, and the contextual interpretation, plus a CI for effect size.

4.2.4 Solved Exercises

Exercise 1

Without finding the values, arrange the numbers from small to large:

- \(P(Z < -1.40)\)

- \(P(T < -1.40)\) with \(df=9\)

- \(P(T < -1.40)\) with \(df=14\)

- \(P(Z > 1.20)\)

- \(P(T > 1.20)\) with \(df=9\)

- \(P(T > 1.20)\) with \(df=14\)

\[ \_\_\_\_\_\_ < \_\_\_\_\_\_ < \_\_\_\_\_\_ < \_\_\_\_\_\_ < \_\_\_\_\_\_ < \_\_\_\_\_\_ \]

Solution

Recall that the t-distribution has heavier tails than the z-distribution, so probabilities farther from the mean will be larger for t. Also, as the degrees of freedom increase, t becomes closer to z.

Smallest to largest:

\[P(Z < -1.40) < P(T < -1.40, df=14) < P(T < -1.40, df=9) < P(Z > 1.20) < P(T > 1.20, df=14) < P(T > 1.20, df=9)\]

Exercise 2

Use R calculator to find the values of the probability of t-distribution. Sketch the t-curve and shaded region.

- \(P(T < -1.40)\) with \(df=9\)

- \(P(T < -1.40)\) with \(df=14\)

- \(P(T > 1.20)\) with \(df=9\)

- \(P(T > 1.20)\) with \(df=14\)

Solution

pt(-1.40, df=9) # 0.0948

pt(-1.40, df=14) # 0.0905

pt(1.20, df=9, lower.tail=FALSE) # 0.1266

pt(1.20, df=14, lower.tail=FALSE) # 0.1233Exercise 3

Use R calculator to find the critical t-value \((t_{\alpha/2})\), rounding to 4 decimal places.

- CL = 90%, \(n = 9\)

- CL = 98%, \(n = 22\)

- CL = 99%, \(n = 30\)

- CL = 95%, \(n = 11\)

Solution

Degrees of freedom \(df = n - 1\).

qt(0.95, df=8) # 1.8595

qt(0.99, df=21) # 2.5176

qt(0.995, df=29) # 2.7564

qt(0.975, df=10) # 2.2281| Confidence Level | df | \(\alpha/2\) | \(t_{\alpha/2}\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90% | 8 | 0.05 | 1.8595 |

| 98% | 21 | 0.01 | 2.5176 |

| 99% | 29 | 0.005 | 2.7564 |

| 95% | 10 | 0.025 | 2.2281 |

Exercise 4

Find confidence intervals using the following sample information:

- \(n=6, \bar{x}=5.3, s=1.5\), 90% confidence level

- \(n=18, \bar{x}=5.3, s=1.5\), 90% confidence level

- \(n=6, \bar{x}=5.3, s=1.5\), 98% confidence level

- \(n=18, \bar{x}=5.3, s=1.5\), 98% confidence level

# (a)

t_a <- qt(0.95, df=5); ME_a <- t_a * 1.5/sqrt(6)

c(5.3 - ME_a, 5.3 + ME_a)

# (b)

t_b <- qt(0.95, df=17); ME_b <- t_b * 1.5/sqrt(18)

c(5.3 - ME_b, 5.3 + ME_b)

# (c)

t_c <- qt(0.99, df=5); ME_c <- t_c * 1.5/sqrt(6)

c(5.3 - ME_c, 5.3 + ME_c)

# (d)

t_d <- qt(0.99, df=17); ME_d <- t_d * 1.5/sqrt(18)

c(5.3 - ME_d, 5.3 + ME_d)| Case | df | CL | \(t_{\alpha/2}\) | Margin of Error | Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | 5 | 90% | 2.015 | 1.23 | (4.07, 6.53) |

| (b) | 17 | 90% | 1.740 | 0.62 | (4.68, 5.92) |

| (c) | 5 | 98% | 3.365 | 2.06 | (3.24, 7.36) |

| (d) | 17 | 98% | 2.567 | 0.91 | (4.39, 6.21) |

Exercise 5

What factors influence the width of a confidence interval?

Solution:

Confidence level: Higher confidence \(\Rightarrow\) wider interval.

Sample size (n): Larger \(n \Rightarrow\) smaller standard error \(\Rightarrow\) narrower interval.

Sample variability (s): Larger \(s \Rightarrow\) wider interval.

From Exercise 4, increasing \(n\) narrows the interval, while increasing the confidence level widens it.

Exercise 6

A 95% confidence interval for \(\mu\) is given as (22.50, 23.70) based on a sample of 49.

Find: (a) \(\bar{x}\) (b) Margin of error (c) \(t_{\alpha/2}\) (d) Standard error (e) Sample SD

mean <- (22.50 + 23.70)/2 # 23.10

ME <- (23.70 - 22.50)/2 # 0.60

t <- qt(0.975, df=48) # 2.010

SE <- ME / t # 0.2985

s <- SE * sqrt(49) # 2.09

mean; ME; t; SE; sExercise 7

Find the P-value for the given sample sizes and test statistics:

- \(n=24\), \(T=2.315\), right-tailed

- \(n=16\), \(T=-1.60\), left-tailed

- \(n=24\), \(T=2.315\), two-tailed

- \(n=16\), \(T=-1.60\), two-tailed

# a

1 - pt(2.315, df=23) # 0.0159

# b

pt(-1.60, df=15) # 0.0653

# c

2*(1 - pt(2.315, df=23)) # 0.0318

# d

2*pt(-1.60, df=15) # 0.1306| Case | Tail | P-value | Decision (\(\alpha=0.05\)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | Right | 0.0159 | Reject \(H_0\) |

| (b) | Left | 0.0653 | Fail to reject \(H_0\) |

| (c) | Two | 0.0318 | Reject \(H_0\) |

| (d) | Two | 0.1306 | Fail to reject \(H_0\) |

Exercise 8

A random sample of 25 Seattle residents reported their daily coffee intake:

\[ n = 25, \quad \bar{x} = 2.7, \quad s = 0.9 \]

A nutritionist claims that Seattle residents drink more than 2 cups per day on average.

Is the result statistically significant?

Follow the steps to conduct the hypothesis test.

- Write the hypotheses

\[ H_0: \mu = 2 \\ H_a: \mu > 2 \]

- Calculate the test statistic

\[ T = \frac{\bar{x} - \mu_0}{s / \sqrt{n}} = \frac{2.7 - 2}{0.9 / \sqrt{25}} = \frac{0.7}{0.18} = 3.89 \]

(c) Compute the P-value and draw a picture

- Conclusion (using \(\alpha = 0.05\))

Since \(P < 0.05\), we reject \(H_0\). There is strong evidence that Seattle residents drink more than 2 cups of coffee per day on average.

- Confidence interval interpretation

A 90% confidence interval corresponding to this hypothesis test would not include 2, which supports the conclusion from the hypothesis test.